Wellness vs. PubMed, Vol. 3: Will intense exercise spike my cortisol?

Hop on the Magic School Bus into our bodies and PubMed as we look around at the nuance of TikTok's demonized "stress hormone" and exercise

Hello, and welcome back to another deep dive into the process of exploring the literature behind trends in the wellness world. I take joy in doing this for my own human experience, and I’ve loved bringing you all along so far. Something I am learning as I write these is how to pick a salient, specific question to address a broader trend. I have four drafts trying to pick apart the cortisol trend gathering dust, and part of that is because it was too general. One of my big misgivings with the Wellness Industrial Complex is that it often relies on the opacity of either a degree of the person talking OR on “the research says” without actually talking about WHAT research they are citing OR who their expert is. So, for today’s post, dear reader, we are going to HAVE A FOCUS (so feasibly you can disagree with points of research or data I lay out here).

As always, this is meant to serve as an exploration of the claims of the non-regulated wellness industry, and not as direct or personalized medical advice. We are hoping to increase health literacy so that when you have access to healthcare, you can ask more specific questions in the limited time you have. Please listen to your personal physicians, clinicians, and professionals in guiding your own healthcare decisions (not a random person on the internet, even if you trust me).

Point 1: What do we mean when we say cortisol?

I will let the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology start us off on our basic terms.

“Cortisol is your body's main stress hormone. It helps control your metabolism by regulating how fats, proteins, and carbohydrates are made, stored, and broken down. It also suppresses inflammation, regulates the immune system, helps to maintain blood pressure, increases blood sugars, and controls the sleep/wake cycle. Cortisol is produced and released from your adrenal glands, which sit on top of your kidneys.”1

Cortisol is not a solo act—hardly anything in our bodies are. Cortisol most notably is regulated and helps regulate what is known as the HPA Axis, aka the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis. The Cleveland Clinic notes this as, “The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is a communication system between three organs. It’s crucial for your body’s stress management. These endocrine system organs create a feedback loop of hormones to enact and regulate your body’s stress reaction.”2

This is our 101, and you could (and I know people who do) dedicate the better part of 20 years trying to understand this hormone, its cascade of effects, and how it plays with other signaling pathways in the body. It’s not to say, “Let’s throw our hands up and give up, NOTHING is knowable.” Rather, my point with saying this is that anytime someone gives you a simple explanation for a complex, seemingly unsolved in the wider community phenomenon, you should pause, big time. From a scientific lens and as a clinician myself, one of the big beauties and thorny annoyances of working in healthcare is the labyrinthine nature of understanding and treating the body.

Point 2: Why do people online care if their cortisol is high or spiked by certain things?

In theory, dysregulation of cortisol and/or the HPA axis really can and does have negative impact, especially on those with endocrine disorders. In particular, too-much cortisol is known as Cushing’s Syndrome (or Disease, if caused by a pituitary tumor). Too low of cortisol is also a possibility, like if someone is coming off of chronic corticosteroid use or is gravely ill in the hospital, but we will stick with high given the question of “spiking” cortisol.

I’m not an endocrinologist, so I won’t speak further than this. One of the ways cortisol is talked about in Wellness World is via lab tests/screening that have not been validated, generally, by the larger clinical community. This can happen for a number of reasons including tests not being specific, sensitive, or clinically relevant enough for expanded use. Even in the research/experimental world, the best test isn’t always clear, especially with a hormone like cortisol that has inherent diurnal rhythm (ie it’s normal for it to be at different levels at different times of day).

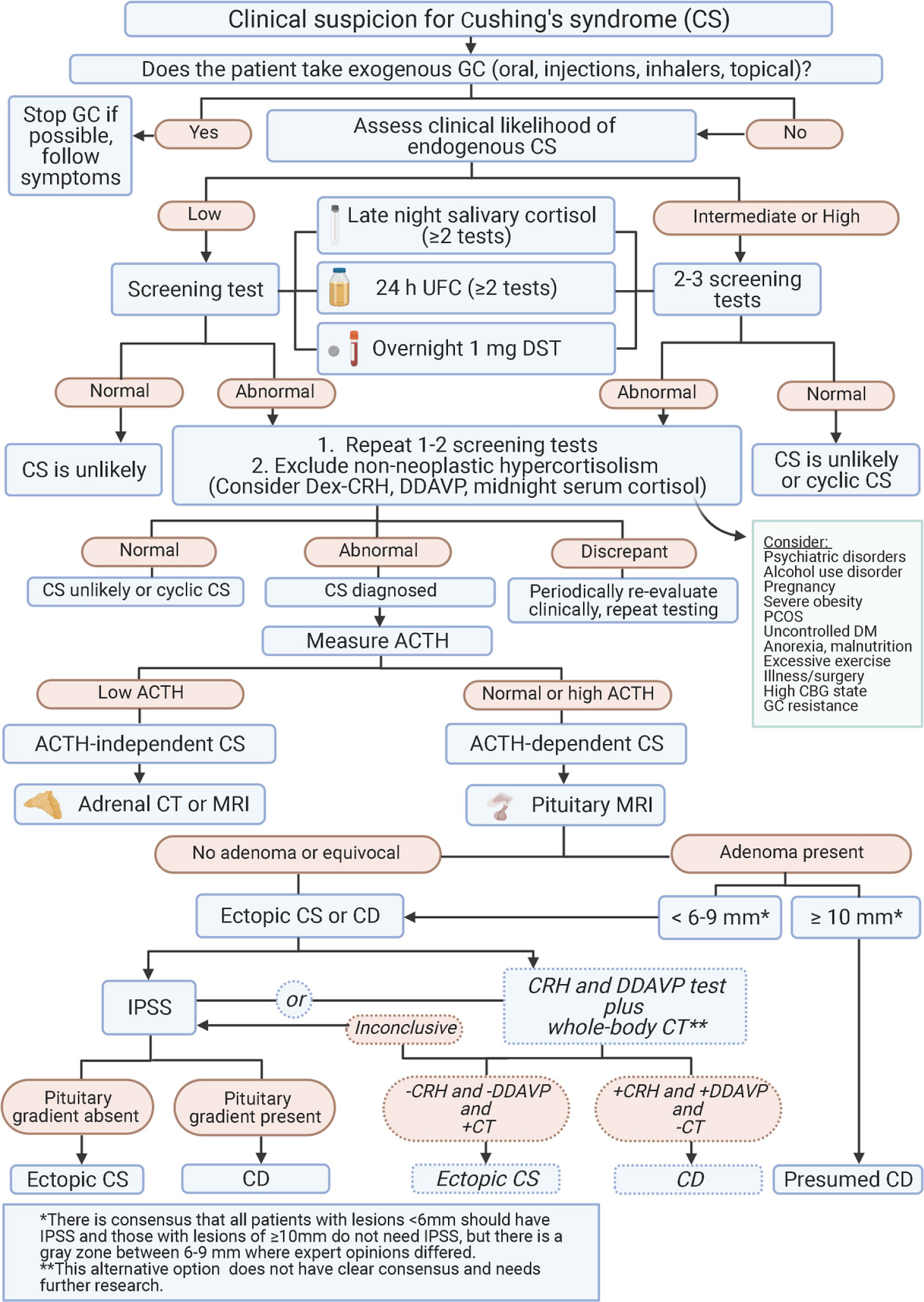

When we look at a lab test, we get the “normal limits” from larger studies that associate a certain lab number with certain symptoms, X% of the time. I’m not going to go further into this, and you don’t want to and shouldn’t try to read the following chart, but this is from the recent clinical guidelines3 that gives a general, simplified outline of how an endocrinologist thinks about confirming “too high of cortisol.”

In addition to explicit endocrine/hormonal illness, there are more subtle indications that the HPA axis (and cortisol) are part of mental illness4 and autoimmune illness. “Inappropriate regulation of the stress response has been linked to a wide array of pathologies including autoimmune disease, hypertension, affective disorders and major depression.”5 It is known that excess cortisol can and does impact organ systems throughout the body, including immune system suppression (which is why we use it in autoimmune conditions), reduced wound healing, reduction in bone health if taken chronically, as well as anxiety, psychosis, and others.

Unfortunately, the research literature does not have answers for us yet on how to clinically use this correlation day-to-day, outside of the usual boring but effective stress-reduction techniques, like optimizing sleep, generally eating a diet with produce, enough calories, and a good amount of varied micronutrients, connecting with our bodies via movement, mindfulness practices, and meaningful relationships.

All in all, this means that it makes sense for people to be concerned with their stress systems, cortisol, and its connection with overall wellbeing. However, what the research doesn’t yet support is a clear supplement, exercise program, or other wellness product to meaningfully attenuate this.

If you’d like a conversation discussing endocrinology and the Wellness World with nuance, this episode of Food Psych is a conversation between a dietician (RD) and endocrinologist6. Linked here, and in citations.

Point 3: Is intense or high-impact exercise really causing my hormones to be out of balance?

In the past year or two, part of the Cortisol Discourse has been regarding the idea that high intensity exercise, like HIIT or bootcamp style classes, are inherently bad for your hormonal health and ~balance~. The assertion is that during and immediately after such exercise, cortisol levels are raised, and that this can be related to symptoms of fatigue, pain, injury, bloating (?), illness, depression, lethargy etc as well as the symptoms from above described in Cushing’s (and, of course, the most feared on TikTok: “Moon Face.”)

I think the paper that many people (including at least one in my TikTok video that went viral comparing cortisol/pilates craze to how historically women were told that vigorous exercise would make their uterus move around or prolapse) was this one from the Journal of Endocrinology in 2008.7 The paper is highly cited (1000+), and discusses the impact of different intensities of exercise on blood cortisol and ACTH taken immediately prior and immediately after exercise. In this paper, they conclude that immediately post exercise, higher intensity exercise raises circulating cortisol levels, and lower intensity exercise did not, and may lower circulating levels, hence the title of threshold effect.

This paper was written with contribution by A.C. Hackney, which is important, as Hackney also co-authored a paper 5 years later in 2013, in which the following is stated regarded cortisol:

“Glucocorticoids, specifically cortisol, are considered stress response hormones, which in an overly simplified view, are often portrayed as being entirely negative in their influence on physiological function. The glucocorticoids are in fact vital hormones in the normal physiological functioning of humans, and they are necessary in dealing with different stress challenges to the body. With respect to exercise, they play an important regulatory role in metabolic responses. Additionally, the regulation of protein turnover during the recovery from exercise, which is instrumental to the myoplasticity response of skeletal muscle in training, is dependent upon appropriate glucocorticoid actions. In other words, cortisol and the other glucocorticoids are not the “bad guys” of exercise endocrinology as some have made them out to be. Researchers, athletes and sports coaches need to be aware of the critical nature of glucocorticoids to normal health and development, especially relative to exercise training adaptations.”8

Finally, we must take the perspective of the forrest over the trees in this. Which gets me to our final point: Stressors, at the right dose, with enough good sleep, and often with a good coach, may actually lower our overall stress and basal cortisol OR show a positive adaptation via our body’s stress system, and decrease the likelihood that future similar stressors will cause a negative or overwhelming response. This all depends on type and intensity of exercise, the person’s training level, comorbidities, and more, but if you’re interested and want to nerd out, here is a review on exercise and cortisol and other hormonal regulation.9

Final Points…

If approaching exercise or nutrition in a way that cares about cortisol has helped you, in your own life, without negative impact on you, I think that’s great! Often, these programs or products are advertised alongside promoting better sleep, mindfulness exercises, and trying to reduce stress. If it works for you, I love it.

When there are chronic, difficult, and not yet readily explained symptoms, it can leave a vaccuum for the Wellness Machine to fill with promises of fixing with their very special product or program. I’m writing about this so you can have a better chance of both saving money and, sometimes more importantly, saving the time you might use chasing one of these promises to actually get better sleep, work on stress reduction, or just do something you enjoy.

Listening to your body, your sense of overexertion, fatigue, or just straight up not liking a form of movement? Love that, and recommend that. People’s stress should be taken more seriously, and the positive part of this trend is people taking more into mind that recovery and rest are also part of caring for themselves.

Thanks for reading, and see you on our next Wellness vs Pubmed Showdown!

Cortisol definition by the AACE: https://www.aace.com/disease-and-conditions/cushings-syndrome/aace-patient-guide-rare-endocrine-diseases-cushings-syndrome

Cleveland Clinic HPA Axis: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal-hpa-axis

Fleseriu M, Auchus R, Bancos I, Ben-Shlomo A, Bertherat J, Biermasz NR, Boguszewski CL, Bronstein MD, Buchfelder M, Carmichael JD, Casanueva FF, Castinetti F, Chanson P, Findling J, Gadelha M, Geer EB, Giustina A, Grossman A, Gurnell M, Ho K, Ioachimescu AG, Kaiser UB, Karavitaki N, Katznelson L, Kelly DF, Lacroix A, McCormack A, Melmed S, Molitch M, Mortini P, Newell-Price J, Nieman L, Pereira AM, Petersenn S, Pivonello R, Raff H, Reincke M, Salvatori R, Scaroni C, Shimon I, Stratakis CA, Swearingen B, Tabarin A, Takahashi Y, Theodoropoulou M, Tsagarakis S, Valassi E, Varlamov EV, Vila G, Wass J, Webb SM, Zatelli MC, Biller BMK. Consensus on diagnosis and management of Cushing's disease: a guideline update. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021 Dec;9(12):847-875. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00235-7. Epub 2021 Oct 20. PMID: 34687601; PMCID: PMC8743006.

Citation: Dziurkowska, E.; Wesolowski, M. Cortisol as a Biomarker of Mental Disorder Severity. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5204. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10215204

Ramamoorthy S, Cidlowski JA. Corticosteroids: Mechanisms of Action in Health and Disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2016 Feb;42(1):15-31, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2015.08.002. PMID: 26611548; PMCID: PMC4662771.

Conversation on myths on Hormone Health on Food Psych. https://christyharrison.com/foodpsych/10/hormone-health-myths-and-facts-with-endocrinologist-gregory-dodell

Hill, E.E., Zack, E., Battaglini, C., Viru, M., Viru, A. and Hackney, A.C., 2008. Exercise and circulating cortisol levels: the intensity threshold effect. Journal of endocrinological investigation, 31, pp.587-591.Vancouver.

Hackney AC, Walz EA. Hormonal adaptation and the stress of exercise training: the role of glucocorticoids. Trends Sport Sci. 2013;20(4):165-171. PMID: 29882537; PMCID: PMC5988244.

Athanasiou, N., Bogdanis, G.C. & Mastorakos, G. Endocrine responses of the stress system to different types of exercise. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 24, 251–266 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-022-09758-1