How To Escape the Beauty Panopticon

Wellness vs Pubmed Vol. 5: What we can learn from the literature on body dysmorphia and body image to help us enjoy exercise more

There’s a saying attributed to C.S. Lewis about the virtue of humility, and I often think of it when I think about my patients who struggle with body image.

“Humility isn’t thinking less of yourself. It’s thinking of yourself less.”

If I could sum up what the goal of treatment for Body Dysmorphic Disorder is, it would be that—simply thinking about how one appears less often.

Body Dysmorphic Disorder (or BDD) lives in the chapter of the DSM5 entitled, “OCD and Related Disorders.” For anyone who has BDD or OCD, or knows someone who does, it is readily apparent that the pain of these conditions is from how often images, thoughts, and emotion intrude upon one’s day-to-day life. Living with BDD after an effective treatment doesn’t necessarily mean never have self-critiquing thoughts or insecurities again, but that the amount of life it takes up is reduced to a much smaller portion.

In the same way that everyone experiences the emotion of anxiety, but not everyone has an anxiety disorder, so too do occasional moments of disliking one’s appearance have mean BDD is present. In a culture with strict ideals around what the male or female body “should” look like and punishing morality around those who do or don’t embody that ideal, it becomes difficult to know what a “normal” amount of thinking about one’s body actually means. If you are consuming content online, particularly lately on TikTok, the normalization of fixation with appearance may become more common.

On survey data, 20-40% of women reported being dissatisfied with their bodies.1 Men also struggle with their image and appreciation of their bodies, particularly when defined in satisfaction with level of muscularity. In combination with this, women have been found to place more importance on appearance, and orientation towards their appearance, than men.2 This research isn’t particularly surprising when one takes into account the fact that up until recent decades, women were discouraged from working or providing for themselves, and therefore their sexual and romantic value was the tool with which they could attain security for themselves and their families. It makes sense that women, especially given typical gender role socialization in the US, pay more attention to appearance.

Within the world of BDD, eating disorders, and women’s mental health, a discussion in conjunction with feminist theory often occurs. This is the idea of socialization of girls and women to view their bodies as an object, rather than an alive, experiencing subject. The self-objectifying view is rampant in our culture, and it can normalize viewing one’s body from an outside view of the self, rather than experiencing the sensation and lived moments of being your body. This is what becomes the Beauty Panopticon—we internalize the idea that our value is in how our bodies can be seen and consumed by others, and we ourselves are the critical intern guard and enforcer.

If you are reading my Substack, I would guess this information won’t be new to you, Dear Reader. I circle us back to this to ground us for a bit more around what happens in therapy that is for people struggling with body dysmorphia, and how we might be able to apply some of these concepts in our own lives if we struggle with body image concerns or simply want to reject the visual narratives that are circulating more and more online right now (yes, this is another post inspired by #SkinniTok).

How Therapists Help With Body Dysmorphia + Body Image Concerns

Tools that we use, teach, and practice in therapy are studied to be effective for the specific issue in question, and this is true for those struggling with Body Dysmorphia. These tools are often not just useful for those with a clinical level diagnosis, but can also be helpful for those who are only mildly struggling but want some idea that can help them with it, even if they don’t have access to a therapist or time for it in their life at the moment.

When a patient has BDD, one of the first things we do in reviewing their story in therapy is finding out where these self-judgments, checking appearance, and response behaviors interrupt their life most. As someone trained in the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy model of therapy, I also tend to explore their values and most important part of their daily life, and try to find with my clients where the anxiety and obsessions are most getting in their way, ie in disrupting function. This is usually the place we start, as it’s the most motivating intrinsically to the client.

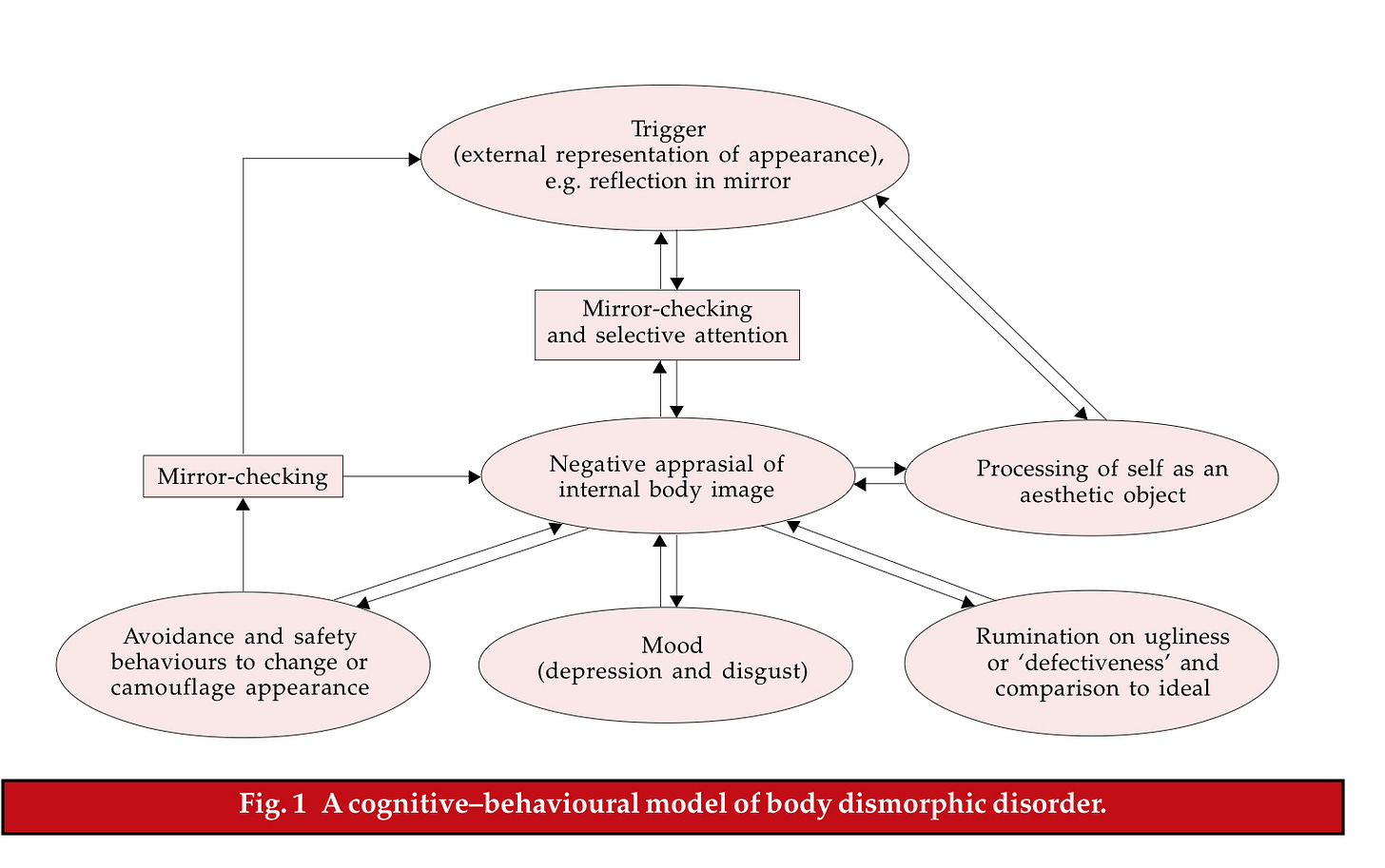

Below is a helpful schematic from a 2001 review paper on BDD3, and how the cognitive and behavioral treatment approach helps frame what is often occurring for patients.

In treatment, we can address almost anywhere on this diagram. For example, as a psychiatrist, if someone also has had a history of episodes of depression, we may medicate with something like Prozac or Zoloft, ie an SSRI. If there was a high identification with the story of the self mainly as an aesthetic object, we may purposefully explore values and the larger narratives around how they value others they love (which often has a more expansive definition than appearance alone), or other parts of themselves they do value. For mirror-checking, let’s say with staring at their skin in the mirror for an hour each night (despite it making them feel worse, not better as they had felt it might), we may work on decoupling the feeling of anxiety around their appearance, and the temporarily-relieving, but long-term intensifying compulsion towards mirror checking.

How These Ideas Can Help Us Opt Out of Self-Objectification Online Discourse

Given the above way of thinking about how we help those with BDD, we can now ask the question of how any person might apply some of this understanding to help themselves deconstruct from viewing themselves as an object, and be more able to enjoy exercise, movement, and play more.

Notice the words and promptings that group fitness classes use.

Though this has, in general, gotten better and less frequent, there are still many fitness environments that use explicit language around making your body look better. While I think we should not judge ourselves too harshly for being motivated by that, I also think we can take note and ask whether this is helping us feel better and be kinder to ourselves in the long run. If it happens 3x a week for a class, that is usually about 3 hours a week you are being taught to step outside of the sensation of exercise and take the voyeur’s view of yourself. This amount of time can be impactful, and make you associate all exercise more with the cue to evaluate the appearance of your body.

Ask whether a mirror is necessary.

There are certainly uses in fitness for mirrors, especially when you are learning new moves where form is important for both efficacy and safety. However, once you’ve learned a move or when you already know what you’re doing, does a constant mirror in front of you actually make the workout more effective? For cardio classes, do you have to stand in a place close to a mirror, or might it feel better over time to have less of class spent evaluating yourself there?

The purpose isn’t to avoid mirrors at all cost, as this can go to the point where your own image is a trigger for anxiety. The middle option—the option of practicing feeling sensation, being in a social group, and trying to learn and feel skills more—can help teach you to do exercise as a moment of connection rather than judgment.

Try to note and float the idea to compare.

When you are exercising, comparison is really the thief of a good time. Whether you are in a studio class and start comparing your body to the girl on the reformer next to you, at the gym and doing a stairmaster competition, or at home and comparing your body to the body of the instructor, the urge to compare is strong. You likely already know this isn’t helpful, and what I’m not saying is to now criticize yourself for this thought occurring or view the goal as getting to never having these thoughts pop up. In mindfulness, I often think of the metaphor of the river, with the image being of yourself sitting by the river, which represents your mind, and watching the leaves on it float towards you and then away into the distance. In the metaphor, the leaves are like the thousands of thoughts that pop into your mind each day, and letting them float in the river is the mental action of allowing them to exist without diving into the water, scooping them out, and shoving them under a microscope or trying to run frantically and get all of them out of the river. When you notice your comparison urge, note it, put it on a leaf, and let it float. It might come back—we do it again. This mental exercise is like lifting a weight—we do many reps to get strong at it.

Challenge your “safety” or “camouflage” in tiny, mildly uncomfortable ways.

Often, when I work with someone in exposure therapy, they will have tried many times to “just get over” or “just do” the thing they are anxious or avoidant towards. This can lead to a cycle of, for lack of a better term, locking in and then crashing out. They ask a LOT of themselves, and it is so overwhelming and scary that they do it once and then avoid it for weeks. The most important part of working with a therapist on this can be the kind pacing paired with compassion in doing the very hard work of desensitizing ourselves to something we really fear.

In thinking about exercising and body image, what this might look like would be to little by little try things related to movement that you’re afraid of but that feel like logical steps to being able to do valued actions that the fear has been blocking you off from. Maybe you think it would be AWESOME to be able to go all out dancing in a Zumba class, but you don’t like the way you look in the mirror (it really is the damn mirrors) and you feel stupid when you try dancing (because you are new at it…), so you never go. A graded exposure to this may be trying to do some dancing videos at home for a while (depending on how big the fear is, think weeks to months!), until slowly the idea of going in person becomes less scary. Then, when you go in person, you make space for the fact that this is a big hard step and the first few times may also feel very uncomfortable, but a manageable level of uncomfortable. Over time, this slow and compassionate process gets people places they never thought they could get to in life, or that they thought they’d only be able to get to if they ran themselves like a machine.

Do movement that requires your mind.

When you’re doing exercise that is repetitive or isolated, it can be easy for your blank mind to go quickly to evaluation of your body and judgment. When you do something that requires the activity of your mind, it’s harder for those punishing thoughts to get in. This may mean that if you’re wanting to move more, a prompted yoga class may be better than an hour long jog by yourself. It may mean reformer classes, where you’re just trying to stay balanced on the platform that you don’t have time to evaluate your body shape in the mirror. It may be reconnecting with a form of sport or play, like soccer or walking in a park you love this spring, that makes your mind naturally want to focus on what is present rather than on giving your appearance a report card. While practicing mindfulness or meditation in exercise can be valuable and something to incorporate, we also don’t have to aim at that all the time, especially when anxiety and body-image thoughts are overwhelming us in the quiet.

These are just a few thoughts on how to engage with movement more when body image thoughts make the process difficult for you.As always, though I am a psychiatry resident, this is a reflection on lifestyle habits for those without clinical diagnoses, in reaction to current culture online on bodies and body-judgment. If you are struggling with body image and your mental health, please seek care from qualified experts who can know you in real life and with specificity. Legally: This should not be construed as professional medical advice or personal direction in management of mental health care.

Take care, and as always, thanks for your time and paid support. It makes posts like these possible, and free monthly posts accessible for those who can’t afford to pay.

Sincerely,

Margaret of Bad Art Every Day

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6928134/#B33

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6928134/#B33

https://veale.co.uk/PDf/CBT%20for%20BDD.pdf