Wellness Literacy, Issue 1: What dose of walking do you really need for your hot girl walks?

aka where I use my PubMed Access and you get to have more health literacy around what wellness culture sells us

Welcome to my first post in a series I hope to build into Substack and the eventual Zine, which I am dubbing Evidence-Based Wellness, in which I use my skills working in medicine to discuss a wellness factoid that’s circling the internet, and we review where it came from, what is true, and what’s been exaggerated. For my paid subscribers, this will be in the January edition of the zine, so if you’re wanting to wait for formatting and read the mag all at once, I’d skip this article.

Today we are addressing one of the most popular New Year's resolutions, and that is getting 10k steps a day (I will only briefly touch on people touting 15k steps a day). Now, the point of this series is not to say XYZ wellness thing is BAD BAD BAD, but rather to offer you the nuance of the science where recommendations come from, so that you get more agency AND the understanding of where the science is at, and what might make living in your body more comfortable.

Today, we will be reviewing a large meta-analysis from 20221, that looked at 47,000+ subjects on the correlation between health and walking, specifically steps in a day averages across life spans and risk for mortality (read: likelihood of dying).

One of the reasons this met analysis was done was to enter the conversation that was already ongoing about if 10k steps was truly needed, as it is a bit of pop health advice that has been around for decades now. The 10k number, though, didn’t come from research, but rather from a marketing campaign in Japan for a pedometer. From an article studying older women and walking in 20192:

“It likely derives from the trade name of a pedometer sold in 1965 by Yamasa Clock and Instrument Company in Japan called Manpo-kei, which translates to “10 000 steps meter” in Japanese.”

General truisms in wellness often come from a half truth, or a half-right interpretation of the data, and where there is no data (which isn’t uncommon, especially when it comes to women’s health), there is passed down wisdom. I’ll say here that just because there hasn’t been a study yet does not mean something does not work, but where there are studies, we should take them into consideration.

Back to walking. In the 2019 paper, prior to the 2022 paper, a gap had been identified in what was known about walking and health: What’s the minimum effective dose to impact people’s health in a way that matters (ie, if walking x number of steps only gets you 1 more week of life, the finding can be statistically significant but not clinically or IRL important to you). From this gap, this 2019 study sought to find what’s called the dose-response curve, which gives us an average view of how different “doses” or number of steps for walking correlates with health outcomes.

You may be asking yourself, why does this matter? From a population level, it matters that people have the correct information, as this may inform whether they do any walking, a lot of walking, or no walking at all. If you think, for example, that there are only health benefits when walking 10k or above, and you’re a busy new parent, or someone who struggles with chronic pain, than that high number may feel out of reach, and you don’t try to have a step goal at all. If, however, 5k steps will reduce morality risk by a big percent, you may try. What feels like semantics, when scaled to public health communications becomes either a helpful truth from what we know OR a misleading barrier.

See how I forced you into some public health learning before I gave you the answer? Yes, that was on purpose. Anyhoo, in the 2019 they had around 18,000 women 45+ years old wear step counters for 7 days. They collected this data for different cohorts from 1992-2015 (ie, they get a week of step data for each person). They then compared this step data by following the women as a group for years after the initial data was collected, mainly for mortality (ie, notification of death).

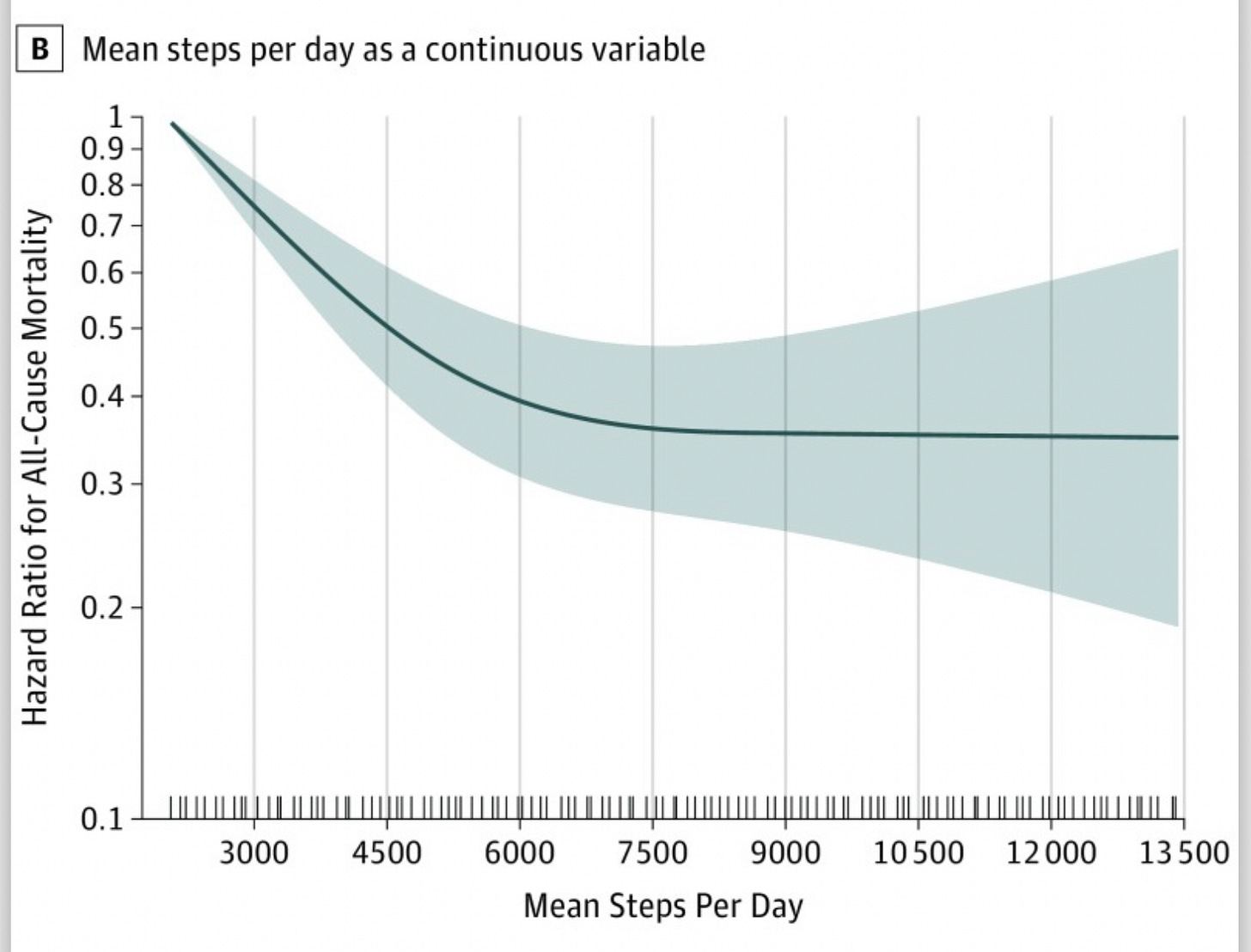

In the table below, you see a dose response curve for these older ladies in the study. Notice at around 7500 steps, the curve levels off, ie there is not a reduction in mortality. It also doesn’t go back up, ie more than 7500 steps is not dangerous or hurting benefits. An additional part of this study was looking to see if pace of walking/intensity mattered, and it seemed intensity change didn’t matter/ got washed out. Volume, aka number of steps, was what mattered.

The second thing I want to point out—As mortality Hazard ratio goes down from the start go the graph until the 7500, which means that ANY increase in daily steps on average will have benefit for health, up until around 7.5k. This means that it is not an either or—4k steps are better than 2k steps, 6 is better than 4, etc. I’m harping on this because the Wellness Industry markets these things in extremes, and with urgency (and usually something to sell with it, like a walking pad).

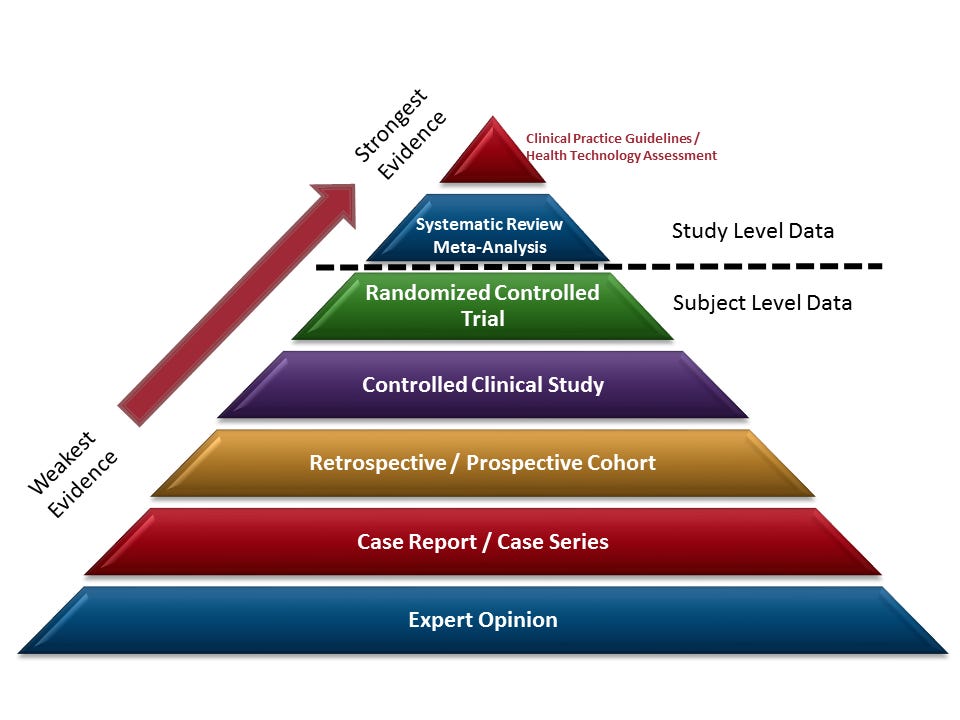

Onto the more recent paper, ie the meta-analysis from 2022. For those not in the science world, a meta-analysis is the gold-standard’s gold standard. Here’s a good image to describe the hierarchy from USF Health Libraries.

That is to say, this meta-analysis is a robust amount of data and covers a large population, so on the scale of bull$hit to trust with your life, it’s one of the most trustworthy sources. This 2022 paper was published in The Lancet Public Health Journal, and The Lancet is one of a few top medical journals. Read: this is like the Vogue of medical studies and opinions.

A meta-analysis takes a bunch of data from a bunch of relatively similar studies to examine findings. In the intro to this study, it adds an important fact from prior studies in different populations on steps: There may be a lower cutoff point for steps for older populations compared to younger. From this paper:

“Findings from large prospective studies have shown mortality risk levels off for older women (aged ≥62 years) at 7500 steps per day5 and among a nationally representative sample of US and Norwegian adults (aged ≥40 years) at approximately 8000–12 000 steps per day.”

The reported purpose for this paper? To take a finer-tooth comb and look at the dose of steps and the impact of each dose range, and how age impacts optimal dose. Importantly, they also included some studies that were not published. In thinking about research, an important concept here is what is known as “publication bias” ie studies that result in no significant change or with very mixed results are less likely to get published than a study with a clear, new, or surprising finding (not just in walking, but across studies).

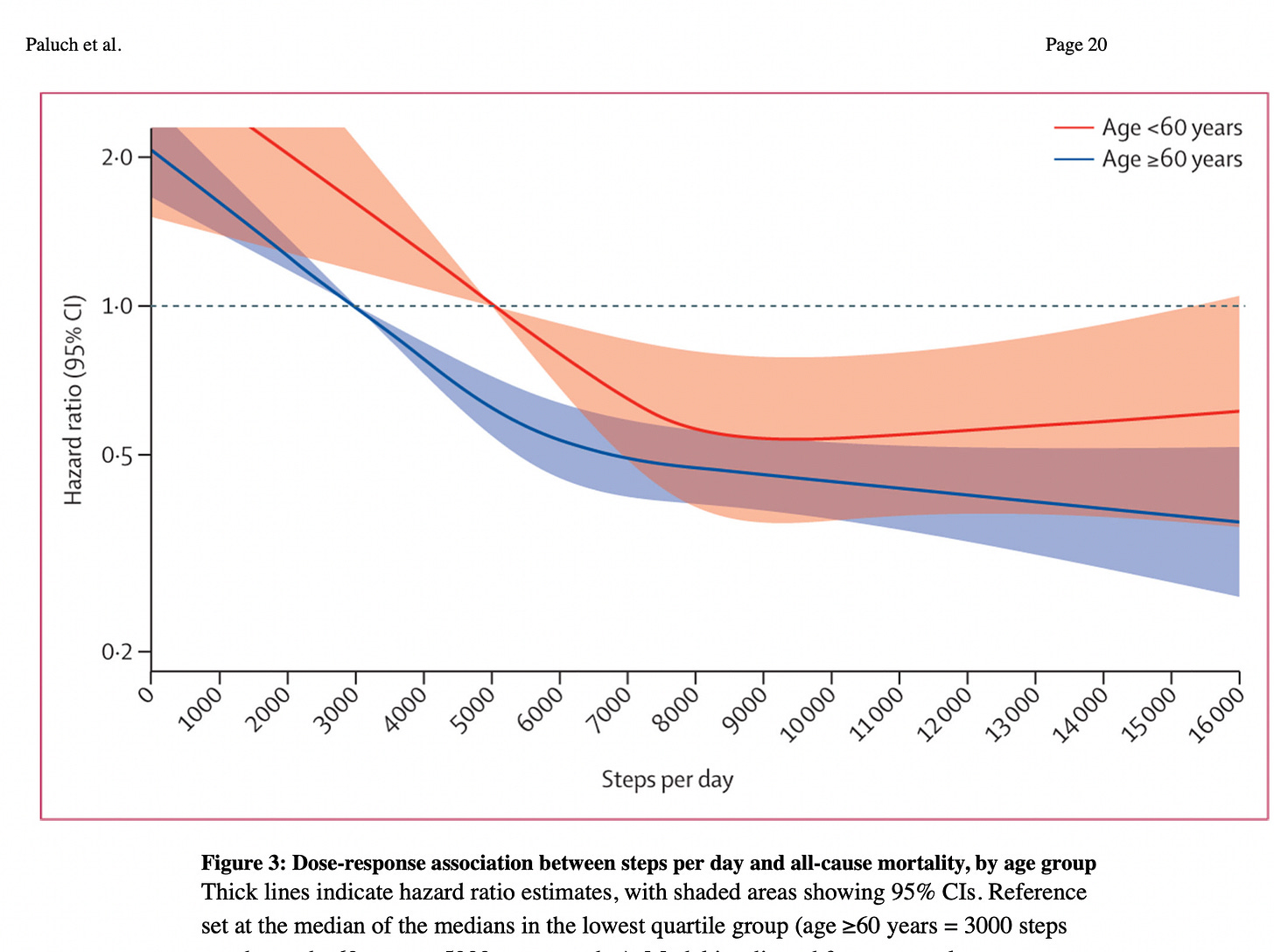

In their results, they share the following delineation, with adults being <60, and older adults being >60. As follows:

“The number of daily steps at which the Hazard Ratio for mortality plateaus among adults aged 60 years and older was approximately 6000–8000 steps per day and among adults younger than 60 years was approximately 8000–10 000 steps per day.”

Later in the paper, they again note the importance of how steep the change is for folks going from less steps (like 3k or less) to moderate to optimal. This is hopeful! Change in health outcomes isn’t reserved just for the optimized, but for all of us hoping to get just a little better.

In the above graph, you’ll also find a correlation (NOT CAUSATION. These were observational studies, not a randomized-control study) for the younger adults ( in red) with a mild return to higher hazard ratio—possibly a correlation between overactivity and negative impacts on health when going towards the 15k step and beyond zone (Please for the love of all that is good, do not aim for 20k steps a day unless you have to or you’re hiking a long long trail this year).

Okay, done with science speak. What can we, my dear readers, take from the science and into our day to day life, Wellness Journeys, and New Year Resolutions?

There is benefit basically every 1k steps you add to your health and mortality probably until around 8k steps, at which point it plateaus, probably same benefit until you get to 15k steps and beyond. This is good—every change has a big impact, so try not to view it as 0 or 10k OR NOTHING.

You likely don’t need 10k to get most of the health benefits. If you’ve already fallen off your hot girl walks because it’s too much and you can’t realistically go from 2000 steps a day to 10k, aim for 7.5 k instead.

Because each change takes time and effort and discomfort to stick, maybe try adding 1k steps to your baseline for a month, and see how you feel.

That is all for this month’s edition of Evidence-Based Wellness. Let me know your thoughts or questions below, and I’ll be sure to answer.

Take care, and enjoy your wintry walks of whatever length, knowing that a little bit of change can still have a large positive impact!

Paluch AE, Bajpai S, Bassett DR, Carnethon MR, Ekelund U, Evenson KR, Galuska DA, Jefferis BJ, Kraus WE, Lee IM, Matthews CE, Omura JD, Patel AV, Pieper CF, Rees-Punia E, Dallmeier D, Klenk J, Whincup PH, Dooley EE, Pettee Gabriel K, Palta P, Pompeii LA, Chernofsky A, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Spartano N, Ballin M, Nordström P, Nordström A, Anderssen SA, Hansen BH, Cochrane JA, Dwyer T, Wang J, Ferrucci L, Liu F, Schrack J, Urbanek J, Saint-Maurice PF, Yamamoto N, Yoshitake Y, Newton RL Jr, Yang S, Shiroma EJ, Fulton JE; Steps for Health Collaborative. Daily steps and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of 15 international cohorts. Lancet Public Health. 2022 Mar;7(3):e219-e228. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00302-9. PMID: 35247352; PMCID: PMC9289978.

Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Kamada M, Bassett DR, Matthews CE, Buring JE. Association of Step Volume and Intensity With All-Cause Mortality in Older Women. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 1;179(8):1105-1112. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0899. PMID: 31141585; PMCID: PMC6547157.

I am so excited for this series!!! I love how you broke down the research.

I do have a question, and I hope you could do the research to answer it. Basically, I started a workout program similar to barre, where there is a lot of repetition of small movements to feel the "burn." From my understanding, this meant my muscles were getting stronger.

When I talked to my partner who has a masters in kinesiology, he said that the "burn" is actually a lack of blood (or oxygen? I was trying to listen LOL) in the muscles. This sensation is actually a different process in your body than when you lift weights and is not as effective for building muscle.

I would love to hear about what the research says for the upsides/downsides for workouts like barre/pilates (minimal weights and focusing on the "burn") as opposed to weight lifting. Is the research broken down into gender specific benefits? I also know that my husband got his degree in 2019, so I was curious to see how the research has changed since then. I hope this makes sense!

Wow this was so helpful to read. Loving your content on here!