Commonplace Books: An Old Practice for a "Brain-Rot" Age

On how Enlightenment era folks made sense of their own "information age", changing culture, and how commonplacing might be the thing that heals our consuming over creating urge

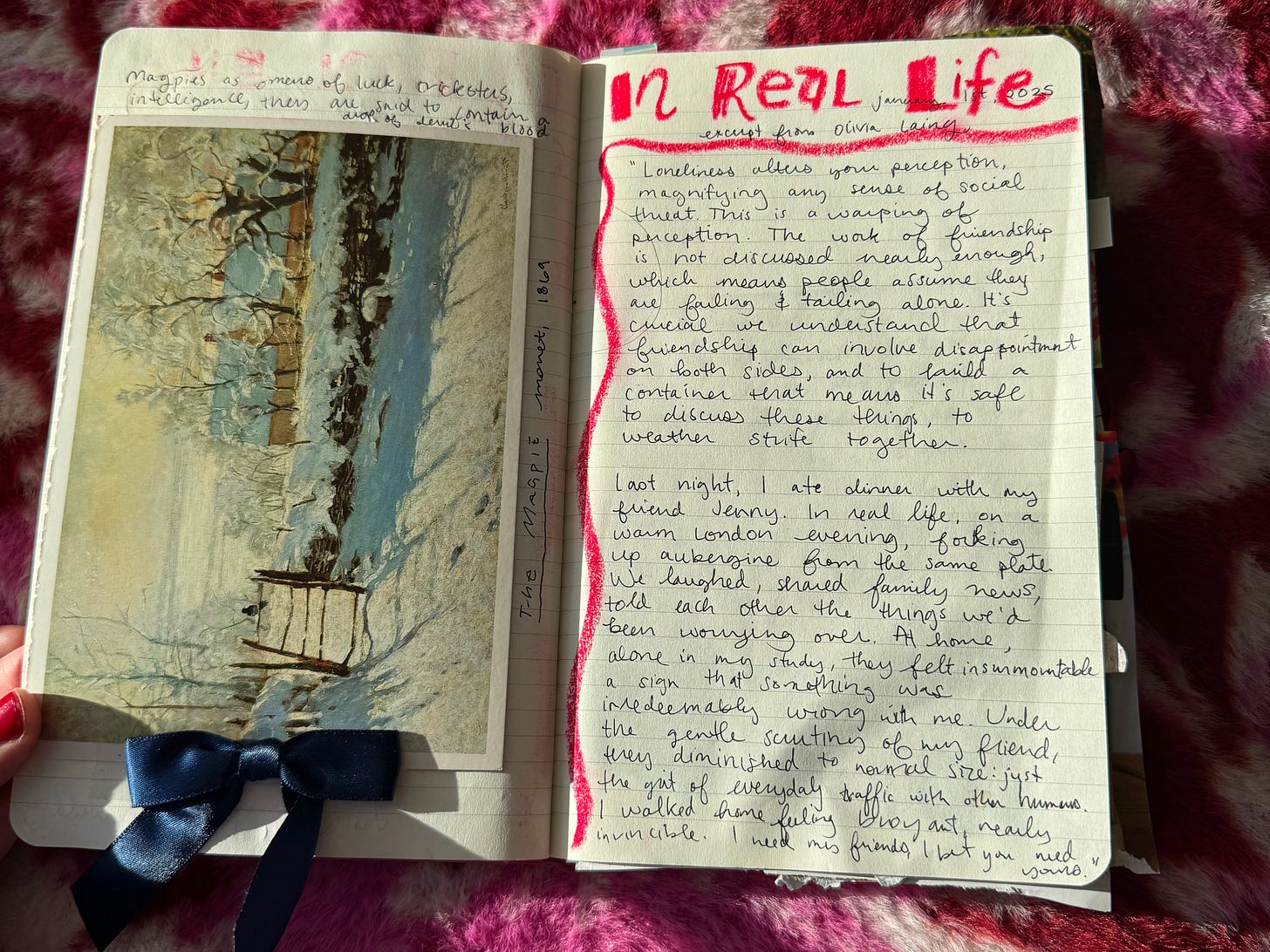

I’m a big fan of a journal, and have loved scrapbooking since I was about 8 years old (I blame my lack of sports talent and that my chore was to cut up scraps of coupons for my mom to earn my allowance). The tactile nature of paper media, but even more broadly with a junk journal, of ephemera that can be made flat and added in between the pages of my little red notebook—this makes me pay a different sort of attention to my life. In a media landscape where our attention spans are the next frontier, practices that bring my attention back to me are valuable.

For a long time, I called my journal a junk journal, and still do at times, because I will put literally anything that strikes my fancy (with delight or disgust) into my notebook. If there’s a will, there’s a way I can glue it in there. However, due to the fact that I read all sort of genres across different time periods, in my recent reading I’ve been re-introduced to the concept of Commonplace books. This is also, naturally, a sequitir others are talking about online and on substack that I’ve seen just a bit of.

As I have learned more about what a commonplace book is, I’ve realized my journaling style may fall readily under this style, and that the history of this style of keeping stock of ideas and feelings is anything but new. Since college, I’ve scribbled down quotes and poems and cartoons from around the internet and whatever book I was reading into its pages, hoping against hope that I’ll be able to recall the gift of that poem or quote when I need it. As an anxious person, I’ve said I need more visual and accessible reminders that silliness and uncertainty are okay, and my journal practices have often been that daily seeking for bits of writing or images that remind me of the world view I wish to hold.

The commonplace book has a long history, coming in and out of intellectual and hobbyist fashion since the 1600s. Its origin story, though, seems to be in response to the felt cultural sense of an overwhelming influx of media—books, print, education, etc, in the Enlightenment period.

The History of Commonplace Books

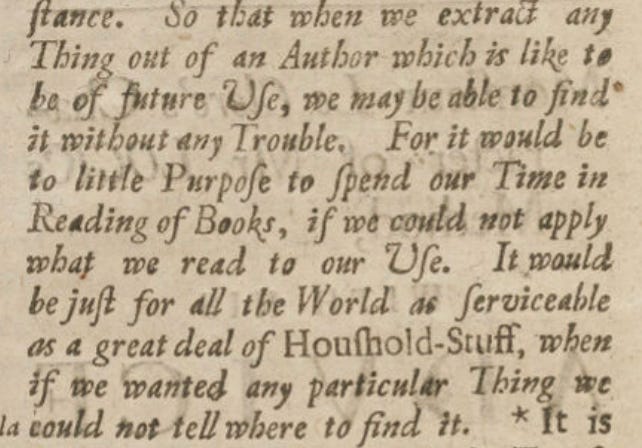

A great article overview I will reference on the history can be found here, on Forte Labs.1 One angle discussed in this article is the idea of these books and “personal information management” systems, or a way of surfing the wave of what felt, at the time, like an exponential increase in access to information.

“ These books helped educated people cope with the “information explosion” unleashed by the printing press and industrialization. They were highly idiosyncratic, personalized texts used to make sense of a new world of intercontinental trade, long distance communication, and mass media. Commonplace books could contain recipes, quotes, letters, poems, tables of weights and measures, proverbs, prayers, legal formulas, notes from sermons, and remedies for common maladies, among many other things.” Forte Labs Article

Per the article, it is thought that the idea of a commonplace resource comes from ancient Greece, in which materials for arguments or reference were kept together for ease of speakers. It pops up again in the 12th century, and again in the 15th century with the theologian Erasmus.

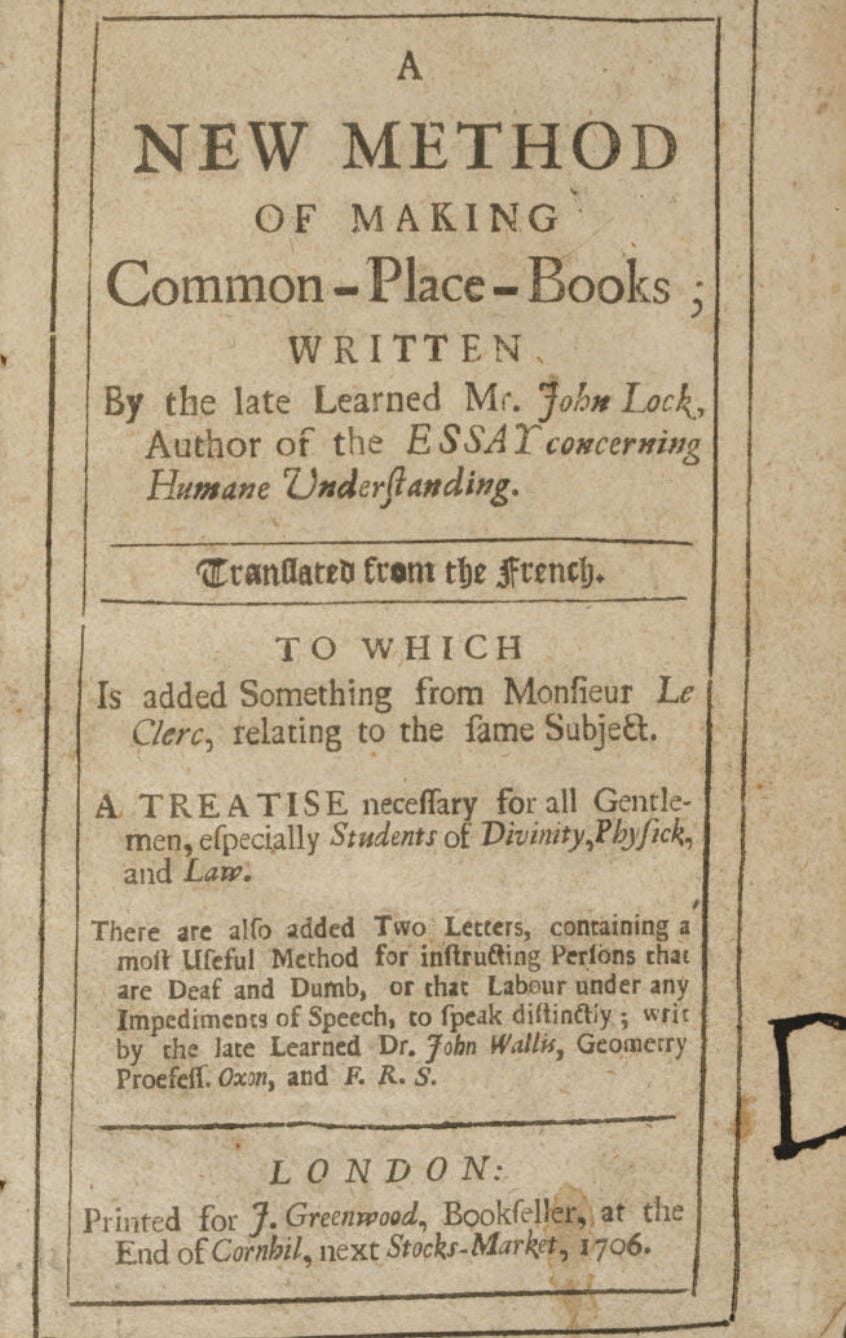

The use of commonplace books, though, wasn’t solidified until a very famous philosopher took up and then evangelized the practice: John Locke. In 1685, he went on to publish a book about his practice, which he had first started doing during his years at Oxford. It was translated to English, by Monfieur Le Clerc, with some additions. It was remarked upon, by colleagues at the time practicing the scientific method, to be odd in that while it had order (an index, with notes from each topic with a heading therein), it was not quite as clearly related and orderly as one might expect from someone who endeavored under logic/rational reasoning as Locke and contemporaries die. From my own personal view, there seems to be a marriage in this method between the two sides of knowing: creativity/flow and reason/order. This is the very thing that makes me love my commonplace book: it gives a relative structure to the small inklings and glimpses of the muse that come, day to day, and gives some form to flighty creativity, but not so much as to smother it.

Much of Locke’s writing and teaching was on the problem of indexing, ie on solving the issue of being able to find again an important bit of learning or inspiration that one had learned prior. I won’t go into indexing, but I do think having a back page with a list of letters, and keeping page numbers, and a general title for things where it makes sense (I, for example, will put poem titles in the index) can be of use, and give a satisfying feel of completeness when you finish a notebook. Also, as stated in the translation, being able to find something again is a big problem (whether because you are at Oxford in the 17th century, or Tik Tok automatically refreshed your feed).

What strikes me about the history of Locke’s use of the commonplace book is that it is a response to a level of cultural and informational change or increase, and this is why I think it useful today, as we live in an informational landscape that too has vastly, unimaginably increased. It feels hard to know things or make use of knowledge when we are being fed media at such an incredible, overwhelming pace.

In the 1800s, it seems there was more updates added to the concept via Bell’s Common-Place Book, which had updated instructions on the method as well as blank pages in it. Think of it as the 1800s version of TikTok’s Five Minute Journal (apologies for comparing 1800s thinkers to Wellness Tik Tok Shop sellers). You can even see what one looked like on this antique site here. Many famous folks from the 18th and 19th centuries kept notebooks in this style. One of whom was Erasmus Darwin, who was Charles Darwin’s Grandpa. These journals, when used to understand history, have helped us understand more broadly the thinking and inspiration important to various important figures.

In reading about Bell’s rules, it would behoove me to note here that Locke was adamant that these books were a structured part of rational exploration, and not journals. I personally will apologize to Locke as being part of the journal-ification of his work. However, what is more notable is not the exact form, at this point in history, but rather what we might learn in 2025 about the process of metabolizing what readers consumed, rather than be consumed by it.

An article from New York Books in 2000 gives a compelling account of more modern “common-placing” in the 1900s, and in this article (which I highly recommend, along with the Forte Labs one), the author reflects on what different commonplace journals reflect, as snapshots of both the larger cultural times and the personal detail that come through via the choices made of what gets included as “excellent” material.

“They broke texts into fragments and assembled them into new patterns by transcribing them in different sections of their notebooks. Then they reread the copies and rearranged the patterns while adding more excerpts. Reading and writing were therefore inseparable activities. They belonged to a continuous effort to make sense of things, for the world was full of signs: you could read your way through it; and by keeping an account of your readings, you made a book of your own, one stamped with your own personality… By selecting and arranging snippets from a limitless stock of literature, early modern Englishmen gave free play to a semi-conscious process of ordering experience.”

Robert Darnton, Extraordinary Common Places, NY Books, 2000

In this piece,2 the author expounds on different academic and non explorations of personality through the later discovery and public access to their commonplace books. In discussing these (mostly male) common-placers, the idea of how reading and consuming metabolizes and connects us to our creative and making side is explored. Online, on Substack, and on Tik Tok, there is a common phrase, “Less consuming, more creating.” Indeed, in my own writing online, I’ve echoed the sentiment. But common-placing has in history and in my own experience been the bridge between consuming and creating.

“They also turned their reading into writing, because commonplacing made them into authors. It forced them to write their own books; and by doing so they developed a still sharper sense of themselves as autonomous individuals. The authorial self took shape in the common man’s commonplace book, not merely in the works of great writers.”

Robert Darnton, Extraordinary Common Places, NY Books, 2000

Darnton explores this way of relating to information as ways of understanding history, and as ways of understanding the fragments that shaped individuals, who then shaped culture. He speaks to the creativity as well as the reflection of society that these books became.

“Commonplacing was like quilting: it produced pictures, some more beautiful than others, but each of them interesting in its own way. The assembled texts reveal patterns of culture: the segments that went into it, the stitching that connected them, the tears that pulled them apart, and the common cloth of which they were composed.”

My Own Commonplacing and Tips for Starting

At 21, I learned about the seismic shift that grief causes when my parent got sick. Since then, I’ve had to become more active in how I populate my brain. This is not a practice of positive thoughts only, but rather, it has been a practice of finding bits of reading and writing, or bon mots", that strengthen, enliven, and make me chuckle each day to help me navigate the world. They are lights in the dark, and they serve as an active archiving and attention exercise to appreciate life—the broad, varied, mixed expanse of it.

My practice for the past almost decade has been morning reading and adding to my notebook. I wake up, and being on my phone or other media stresses me out, even if at first I have the desire to reach for it. I have learned my lesson enough times to know reading or meditation in the morning is the best start for me. But I, it turns out, read in piece meal like the Englishmen of the 1700s did. I keep a stack of books, of all genres, on my coffee table. I pick what appeals. Sometimes I pick a longform saved essay from Substack or a magazine. I settle in with my cup of coffee, and I enter the written world.

At some point in this, and with my journal at my side, something strikes. Sometimes it strikes because it’s beautiful, sometimes it makes me feel a feeling that I don’t know how to label, and sometimes it’s just very weird. This is the taste-making process: the do I like this? I don’t know. Hmm this feels odd, this feels wonderful…". The daily picking out and holding a sentence or phrase or image, turning it over and over, seeing what is there, and seeing what it elicits in your own mind-body. Then choosing something small as a reminder of it, if you yourself find it interesting enough to be in the journal.

As I often write (because I require the constant reminder): the process is the point. The practice is the path. You do end up with an interesting end “product”, a sort of museum to what spoke to you in this year and season of your life. But I feel I get to know my own inner landscape, and have a more playful and exploring view of the world, when I am in a regular practice of creating via commonplacing.

In a world that has so much we could be consuming, so many of us feel inactive, passive, rotting. Yet, when we make promises to change, we try to jump totally away from where we are, desert it, and become people who only make, don’t consume, don’t need inspiration or learning. What if we took a middle way, and incorporated the gifts of the internet and access to info, while also having limits in the physical world—ie, a page a day in your journal? We want to make more of our lives, and that doesn’t mean zero media consumption, but I think it does mean being an active participant in our learning lives.

Forte Labs: Commonplace books: Creative note taking through history. https://fortelabs.com/blog/commonplace-books-creative-note-taking-through-history/

Robert Dalton, Extraordinary Commonplaces. https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2000/12/21/extraordinary-commonplaces/?lp_txn_id=1599046