What Would Mary Oliver Make of AI?

Imagining a conversation with my favorite poet about AI, cottage core aesthetics, and how to be a creative in the social media world

In thinking about creativity, humanity, AI, and nature, my mind has been going back and forth between non-fiction reading on these topics and breaks with the beauty of Mary Oliver’s nature-centric poetry. To explore this more, and to point towards which of her poems I think about related to AI, here is a fictional conversation and my imagined responses of what the poet may have said to advise us. One might call this upmarket philosophical fan-fiction—so be it. My primary source for this is her interview from 2017 in On Being and several linked articles in the footnotes. Here are seven questions I wish we could ask her and seven imagined but informed responses. When I use actual quotes from her from the interview, the words in the piece are italicized.

Question One: You spent your life walking, paying attention, and writing about the natural world, and the lives of the small divinities that live among us. Before we get into the current happenings of the world, I wonder if you might tell us how you’d recommend future or current creatives might live out this spring?

Mary Oliver: Well…I’m a poet, not a therapist, so I’m not sure I can speak to a broad experience. I can speak to how I most often spent my springs, and maybe your readers can take from that whatever they will.

What I loved most about spring was being present enough to see the rapid changes that occur right outside my door. As I’ve said before, I don’t like buildings, so no matter the season in Cape Cod, I would be out there. Spring was a softening, and I knew my small beach and pathways enough over the years to have a sort of kinship with the rabbits, the insects, the way the tides changed just as the first blooms began to came in and the first glimpses of moss emerged. So what I might advise is for people to— as soon as possible— get out of buildings and into nature, and to be there regularly, like it’s a relationship you value—because it can be.

Question Two: Let’s get into our first question about the modern world. What do you make of social media, Mary?

Mary Oliver: You know, that was around when I was still alive, but it hadn’t become the sort of voracious creature I’ve seen it is now. I’ll say something about AI from my experience in learning to write the type of poetry I did.

Many poems are “I did this, I saw this, I said this”, and always I wanted the “I” to be the possible reader, rather than about myself. It was about an experience that happened to be mine but could well have been anyone else’s. It enjoined the reader into the experience of the poem. This way of being with while writing and while creating allowed me to focus on connection with the reader, with the nature I was attending to, and to the creative process itself. When it comes to social media, there are times when it becomes so that the “I” is quite singular, not communal. I would say social media that is about sharing, creating, making art, connecting with loved ones around the world or that inspires you to go out into the world can be a part of a creative’s life. The issue is when it takes up your attention such that there is a narrowing view of your life, or a desire to show only the perfected and disown what is wild, ugly, lonesome within you.

Question Three: How do you think you would use social media if you were alive today as a young poet, trying to get your work out?

Mary Oliver: Oh, I very much advise writers not to use the computer. The habit for creatives all day long is discipline, and we have to have an appointment for that to work out on the page. I used to say I would give my second best labor to the jobs I used to have1, and my first early hours were for writing.

Now, you may think this doesn’t have anything to do with social media, but I think in a creative culture in which the norm is to constantly be in contact with the audience, it’s very easy to lose your ability and energy to be able to listen and create authentically. There has always been something about writing poetry and being in concert with creativity that has required devotion, and the hard thing about making art is actually doing the very boring task of showing up each day and sharpening the ax, cleaning the paintbrushes, writing 1000 lines of bad poetry. Making bad art so that from it the good art emerges, and devoting yourself to that each day as a process. Social media prioritizes the product first in minds of young artists, and that will become a real obstacle to a daily relationship with your creativity if it is not controlled.

If I had to use social media as a new writer, I think I would have a very specific time of the week (not day) during which time I spent a few hours taking pieces from finished work to share, or a process photo that I may have taken (as I often do, for my own delight). I would also be mindful of how much I am consuming, as that can get in the way of listening well.

Question Four: Can you say a little bit more about that? What do you notice in young creatives or young people in general, and what might you advise them about taking in media and information?

Mary Oliver: Certainly. I said, I believe, in my A Poetry Handbook, as follows:

“The poet must not only write the poem but must scrutinize the world intensely, or anyway that part of the world he or she has taken for subject. If the poem is thin, it is likely so not because the poet does not know enough words, but because he or she has not stood long enough among the flowers—has not seen them in any fresh, exciting, and valid way.”

We are always consuming, even before we had these small computers next to our keys, weighing down our pockets. What has changed is the pace at which we take in new things, and the depth to which they stay with us. While I was always reading more poetry, more philosophy (Rumi is a favorite), and having long conversations with friends and with my partner about the world, most of my consumption was limited by time, by imperfection of my conversational partners (and my own inattention), and by availability. In some ways, my consumption was of items that were less consumable, and required more time to process or metabolize. I wasn’t forced to choose between listening to an audiobook about marketing my poetry and going on a walk to listen to the sound of the tides in Provincetown—there was little choice but the walk. I was not as surrounded on all sides as you are now.

If I had to navigate finding sources of learning and inspiration now, I think as with posting on social media as an artist, the artistically-oriented person needs to have limits and structure to how they consume information online as well. You inherit a set of rules of play when you download these applications. Just because there are norms, doesn’t mean they are sensible or worthwhile rules to follow.

Additionally, while excellent art will alter one’s emotional state or consciousness, so too can posts online, and I fear not for the better. While art may evoke negative change in folks, I think more often it aims to open us, to slow us down, to stir us up towards something deeper. It seems social media is made to close us off, polarize, and through algorithms affirm what we already thought. Short, entertaining, and immediately understood information doesn’t grow us.

For those wanting to live a more creative life, consumption also blocks out listening. I once noted a favorite quote from the poet William Blake, who said it as such,

“I have written this poem from immediate dictation, twelve or sometimes twenty or thirty lines at a time, without premeditation, and even against my will.”

I also find myself often having slippery things come to me, a poem emerge fully formed. If consumption and constant noise are our companions, it doesn’t leave much of a door for the poem to come to us, does it?

Question Five: Related to quality of art consumed, I want to move us to the quality of art made, by which I mean human-made versus robot-made. Given the subject and form of your poetry and your relationship to listening with nature, I wonder what you make of how AI is infiltrating the creative space?

Mary Oliver: Like many of you, I believe we as a human community are losing something elemental the more we outsource our lives to AI. Last time I mention A Poetry Handbook, but it keeps coming to mind. In it, one of the topics we discuss is what exactly poetry can or should do. And about poetry is, I think, about life:

“Poetry is a life-cherishing force. For poems are not words, after all, but fires for the cold, ropes let down to the lost, something as necessary as bread in the pockets of the hungry.”

With artificial intelligence, I won’t say there are no right-uses for it. There are parts of life that have tragedy simply through mistakes, mistakes that would benefit from a robot’s ability to proofread. When it comes to AI and the arts, though, it strikes against why I am so devoted to poetry: poetry helps us experience and cherish life. If we outsource a rainy afternoon spent reading by a crackling fireplace, a pot of coffee in the kitchen brewed by your lover, with “my little dog—a heartbeat at my feet” as Edith Wharton used to say—what have we gained? If we lose the ability to slow down and peel the garlic2, chop it and the onion together, let the tear well in our eye as our friend sits at our kitchen table, regaling us with yet another story of a bad date, what have we gained?

There are many parts of using our minds that at first are unsavory, unpleasant, or tedious. Yet, in nostalgia (as I have much of now), it is these very mundane details that come back to us. Artificial intelligence seems to be a path that would block us from discovering what I discovered all those years ago walking the forest paths in Ohio—the small, quiet voice of the wild, and of ourselves.

Question Six: What would you say to those who view your life and romanticize it, or who hear you say how life once was, versus the current tech-filled times? Some have coined you as “very much a cottage-core DIVA” on TikTok.

Mary Oliver: [Chuckles] You know, it isn’t for nothing that I often did those daily walks alone. I did invite others, but my hours of wandering, of intense and one-minded attention, of living in a small town on Cape Cod were certainly off the beaten path, and not enjoyable in the sense many may think of it now. My life was never going to be one that colored within the lines, but it was the life I wanted. Invention hovers always a little above the rules, and in some ways I set up my life by this belief. My life was not one that followed rules, and it was not one that could always be lived publicly before current times.

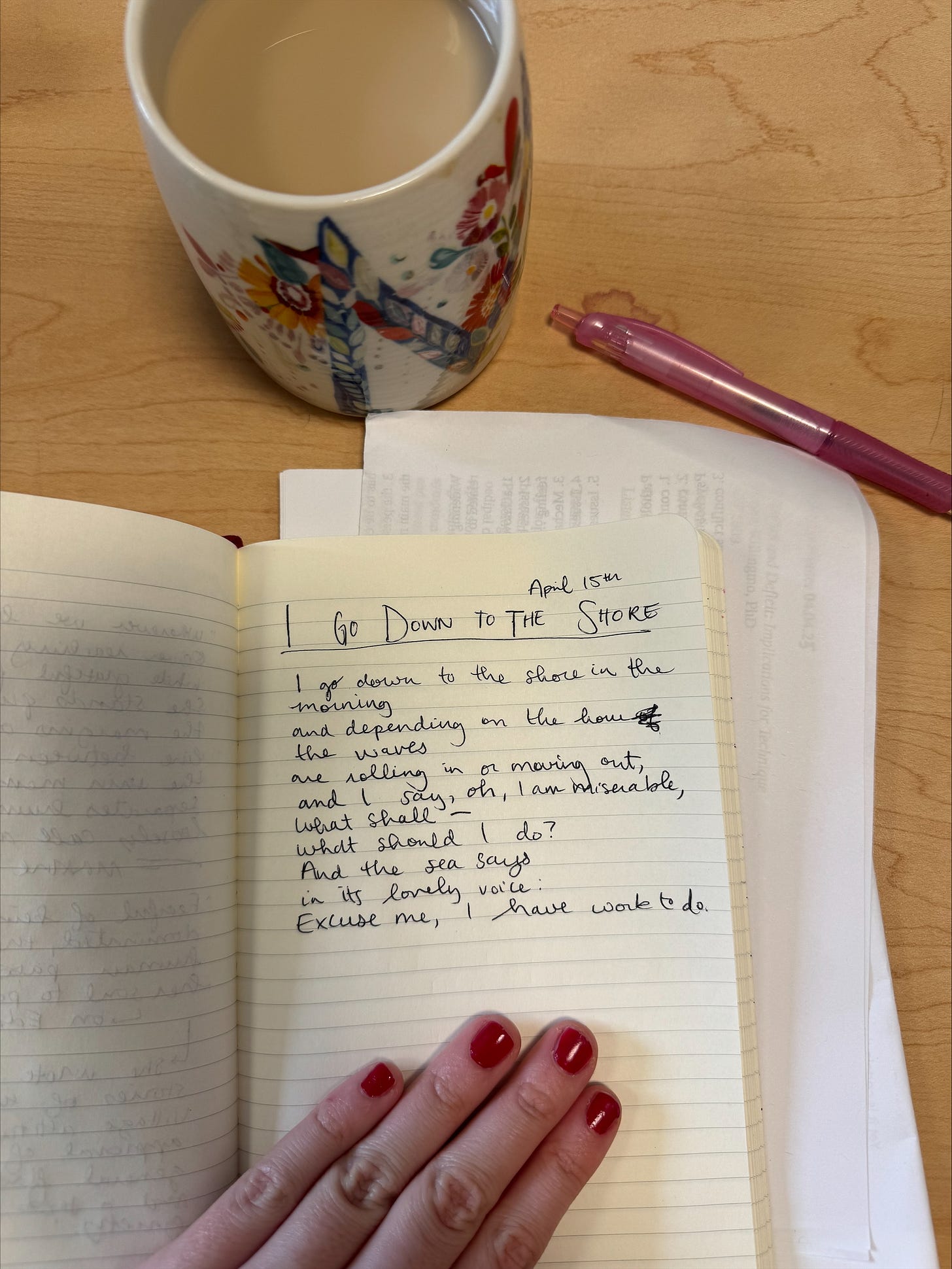

What I would say about those bemoaning the fact that they are 25 years old in 2025 is to read one of my own poems that I often need to re-read myself— “The Shore”. I will not point to what is better about today nor will I point to the tribulations I myself lived through as a way of disincentivizing them. Like my poems, I will let them take what they will from my life, and hope that they come to the shore and get down to the business of trying it out, too.

Question Seven: What would you do on your ideal day in Provincetown, on the Cape?

Mary Oliver: I’ll give you my most ordinary summer day, and know that for the most part the things I do most frequently are the ones I like and need best.

I rise early (famously, now3), as I like to be present on my morning walk in the woods and around the ponds. It is hard to hear many beings speak at once already, without adding human-beings to the mix. On a morning when this goes well, I carry my little notebook with me, and the walk does not get rapid or get anywhere: I finally just stop, and write. That’s a successful walk!”.

I’m often just listening, being present and let whatever comes to me, like the late-leaving moth or creeping early worms, coming upon me only when I am quiet and unobstructive. Sometimes whole poems come to me, rare like a mother and her fawn, proudly presenting themselves once to you on a morning in the woods. More often, I find scraps and fragments, and collect them like those fresh blackbirds, bringing them together into a poem later on.

When I return home, M. is usually still in the kitchen. She’d be making something of whatever the grocer down the street had told her was in season, a side of eggs, some toast, always, always very strong coffee. Sometimes we’d go back out together during the golden and blue hours, walking along the tides or into a cove. She’d go out for the day to the gallery or later her bookstore, where I’d join her later in the afternoon for lunch. After, I’d spend some time in our home cleaning up after our breakfast, and do some logistical work in corresponding with my editor while my dog begged at me to do more important work, such as playing with him. Days often passed where I’d wander or edit, indoors or out, and find myself out by the water digging for clams, reading, or down in town. Over the years, I’ve also become more open with my community, and people in town. I didn’t lock the door for five years. I made many wonderful friends.

All of this—the concrete details of a day—are what make something like a good poem possible. You have to be in the world to understand what the spiritual is about, and you have to be spiritual in order to truly be able to accept what the world is about.

Thank you, imaginary Mary, and thank you, real Mary Oliver, for teaching us in your poetry. Dear Reader—thanks for coming on this fictional interview with me!

Sincerely,

Margaret of Bad Art Every Day

Maria Shriver Interviews Poet Mary Oliver https://www.oprah.com/entertainment/maria-shriver-interviews-poet-mary-oliver/2

The Land and Words of Mary Oliver, the Bard of Provincetown - The New York Times, 2009. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/05/travel/05oliver.html

I reread this twice and I have to say I have such mixed feelings! I think I wish you had not written in her voice- I think it evokes that uncanny feeling that I get when people use the filters to make them look like a deceased celebrity. Or at least I felt strange about it- or about the mixing in of her quotes. I love Mary Oliver a lot so maybe this is just my own reverence butting up against a totally ok thing to do. I felt like it was a strange tonal feeling to try and speak in her voice while also calling out AI and things that attempt to take up the mantle of a person who is no longer with us or an authority cobbled together from all these different sources. Like trying to do the human version of AI. I am not saying it’s bad or something, just that it struck me badly and I spent the afternoon thinking about it and feeling weird.

Ultimately it doesn’t matter what I think but I found myself wishing you were responding to the questions as yourself- I feel more interested in your true answers than your imagined ones as a third party- even a beloved third party. I couldn’t get myself invested in the hypothetical breakfast because it wasn’t real, but then you would sprinkle in a quote and it hops dimensions back into reality for a moment.

I say all this because I am so positively compelled by your writing so often that I found it really troubling to have such a negative reaction, and I wanted to sit with it and figure out why I felt this way. I am glad you wrote the piece and I am very much in favor of experimental writing- even when it becomes a piece that is not my favorite.

And you have inspired me to go and pick up my Mary Oliver book and read a few poems. I hope you have a lovely night.